In our previous article, we delved into verifying the bootstrapping step in Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) within RISC Zero. Building on that foundation, this article shifts focus towards performance optimization.

When people are doing optimization in RISC Zero, the most important lesson is to focus ONLY on the major bottleneck. To know where the bottleneck is, we profile the program by knowing how much “ZK-proving” overhead that each part of the program is contributing to.

This article is dedicated to figuring out this proving overhead—through a combination of theory and experiments over RISC Zero.

Contributing factors of ZK proving overhead

Let us start with the theory. In RISC Zero, the amount of “ZK-proving” overhead is measured in terms of “cycles”. This is in essence similar to cycles of a CPU. Like a regular RISC-V CPU, the cycles in RISC Zero come from mainly two sources: compute and paging.

Compute. Every RISC-V instruction, when being executed, incurs some CPU compute cycles in RISC Zero, as shown below, based on the developer document.

one cycle: LUI, AUIPC, JAL, JALR, BEQ, BNE, BLT, BGE, BLTU, BGEU, LB, LH, LW, LBU, LHU, SB, SH, SW, ADDI, SLTI, SLTIU, SLLI, ADD, SUB, SLL, SLTU, MUL, MULH, MULHSU, MULHU

two cycles: XORI, ORI, ANDI, SRLI, SRAI, XOR, SRL, SRA, OR, AND, DIV, DIVU, REM, REMU

76 cycles per 64 bytes: syscall for SHA-256

10 cycles: syscall for 256-bit modular multiplication

Most of the common instructions—such as those for adding and multiplying 32-bits numbers—incur one cycle. Some of the bitwise operations and division take two cycles. Syscalls, which invoke the cryptography accelerator, take more cycles. This is in essence similar to modern CPU’s SHA extension, which adds instructions dedicated for SHA256 that only take a few cycles to execute.

It is necessary to note that RISC Zero’s cycle counts are specific to RISC Zero—a real-world RISC-V CPU chip is almost guaranteed to have a different cycle count, because computation cost is often higher than the verification cost. Future versions of RISC Zero may also have different cycle counts for each instruction.

However, an instruction may also incur non-compute cycles due to paging, which can also be a significant source of overhead.

Paging. To understand the overhead of paging in RISC Zero, it is useful to first remind ourselves about how modern CPU handles data access, depending on where the data is.

in L1/L2 caches: the data access can be done within a few cycles.

in the main memory: the data access has a latency of hundreds of cycles.

in an external storage: the data needs to be first loaded into the main memory—called “paged-in”, during which the CPU has to wait and it can take more than tens of thousands of cycles even if the external storage is a high-end SSD. Data might also need to be “paged-out” from the main memory back to the external storage.

We call it “paged-in” and “paged-out” because modern operating systems organize the memory that a program can access into “pages”. Page sizes vary from platforms to platforms. In a Mac Studio with M2 chips, each page is 16KB. RISC-V standard uses 4KB. In RISC Zero, pages are smaller, and each page is of 1KB.

In RISC Zero, the program can use up to ~192 MB of space addressed from 0x0400 to 0x0c000000. This space is split into pages each of 1KB. These pages are indexed by a number of page tables, which takes a space of about 6.7MB at the space starting at 0x0d000000. Similar to modern operating systems, page tables are multi-level, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Multi-level page tables for the memory space in a guest program in RISC Zero.

In an RISC Zero program, when a page is being accessed for the first time, RISC Zero needs to “zk-load” this page so that its data is put into an authenticated format that the ZK circuit can use. At the end of the execution, RISC Zero will “zk-unload” the page, which verifies if the page has been modified in a way that is consistent with the ZK circuit execution.

Note that to load or unload a page, RISC Zero needs to load or unload its page table. In other words, the first instruction of the entire program will load 5 pages:

Page A: The page where the instruction is located.

Page B: The 4-th level page table for A.

Page C: The 3-rd level page table for B.

Page D: The 2-nd level page table for C.

Page E: The top-level page table.

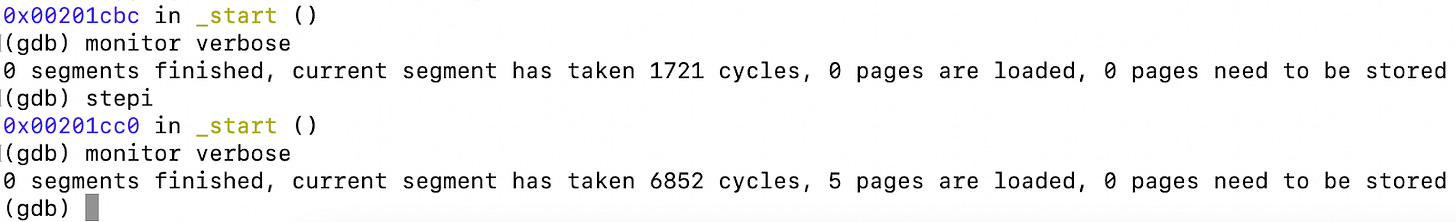

Each page load/unload contributes about 1094 cycles, except for the top-level page table which takes 754 cycles, a little bit less. This can be visualized through a tool—which we will present soon—that allows us to see how the number of pages loaded or unloaded is changed throughout the execution.

Figure 2: Example output from GDB for RISC Zero that illustrates the cycles.

For an RISC-V program running in RISC Zero, the amount of page cycles therefore depends on how many memory pages are accessed or modified throughout the execution—people also call that “memory footprint”. One can see that there is some necessity, in terms of optimization, to avoid using too much memory at a specific time. To put it differently, there is a preference to lower the peak memory in RISC Zero.

Now that we have talked about the cycles, we want to explain why cycles are directly related to the ZK proving overhead. This has something to do with how RISC Zero performs the zero-knowledge proofs. There is not much documentation about the ZK circuit of RISC Zero, but the code is open-source. For us to understand the ZK proving overhead, let us first understand RISC Zero’s ZK.

From cycles to ZK proof

To put it simply, the proof system of RISC Zero can be summarized as follows.

UltraPlonk (or Halo2). The arithmetization consists of customized gates, high-degree polynomial relations, many witness wires, and lookup arguments.

FRI. Polynomial evaluation and commitment is done using fast Reed-Solomon interactive proof of proximity (just call it FRI).

BabyBear. The computation is defined over the BabyBear field (modulus 15 * 2^27 + 1) and a degree-four extension is used during the algebraic holographic proving. Each BabyBear element stores one byte of the data. In other words, a 32-bit integer uses four BabyBear elements.

Memory checking. Although pages are authenticated using the Merkle tree, the main memory uses an algebraic memory checking technique so that each access to the main memory always incurs only a constant overhead.

SHARK from Groth16. Proof generation results in STARK proofs that can be further compressed—without revealing information and in a trustless way—into very succinct SNARK proofs through Groth16. We expect RISC Zero to conduct their setup ceremony for the SNARK circuit over Privacy Scaling Exploration (PSE)’s public ceremony platform, P0tion.

The full circuit of the RISC Zero is available, but the compiler that converts the high-level description into the circuit, called Zirgen, is not released yet. Nevertheless, a few videos from Nethermind and RISC Zero should be able to give you a high-level idea of how the circuit comes from, and why a compiler is needed for efficiency, hardware agnostic, and formal verification.

Note that the summary above about the RISC Zero proof system is just for today. It can be very different in the future. With the development of recursion (previously called “continuation”, but it is more generic now) in RISC Zero, RISC Zero likely will become some sort of “Plonk”, in that people can customize their own application-specific variants of RISC Zero that are tailored for different applications.

One can imagine a future where RISC Zero becomes the hub of different ZK protocols, like Minecraft that has a very large modding/plugins ecosystem with 150k+ community projects. Here, RISC Zero provides general-purpose support and common features—in terms of RISC-V and SHA256/BigInt syscalls—as well as the infrastructure for circuit generation (Zirgen), remote proof delegation and compression (Bonsai), and also efficient implementation for different backends, including CPU, Metal, and CUDA, derived by Zirgen. Executable files from other target platforms—such as WASM—can be converted into RISC-V without much of the VM overhead through just-in-time compilation (JIT), which is similar to Solana’s JIT for VM—rbpf.

Figure 3: A potential future with proof systems built based on RISC Zero.

Previously, the two biggest challenges for people to “Rolling Your Own Crypto” are (1) technical and knowledge barriers to create the proof system (2) insufficient confidence in the security. Fortunately, Zirgen helps with the first, and Nethermind has discussed how it facilitates formal verification. A generation of application-specific, formally verified, community-built proof systems that laypersons can create—probably with the help of GPT—is not far away, and this can be the true decentralization of ZK proof systems, and it removes the “elitism” risk of ZK.

In RISC Zero, there are about six ZK circuits that encode the constraints of RISC-V program execution, each of a different size, as follows.

A circuit that verifies up to 32768 (=2^15) cycles of execution

A circuit that verifies up to 65536 (=2^16) cycles of execution

A circuit that verifies up to 131072 (=2^17) cycles of execution

A circuit that verifies up to 262144 (=2^18) cycles of execution

A circuit that verifies up to 524288 (=2^19) cycles of execution

A circuit that verifies up to 1048576 (=2^20) cycles of execution

To select a circuit for a specific RISC-V program, RISC Zero first runs the program and finds out how many cycles it takes to finish. Then, the smallest circuit that can handle that cycle count is selected. If the execution takes more than 2^20 cycles, the entire execution would be split into segments, each of up to 2^20 cycles, and the segment proofs are merged together through proof recursion.

All these circuits follow a pretty simple structure.

Pre-loading sub-circuit: verify the initialization of the execution environment—the initialization of the lookup tables for byte formality checking and RAM, the initial data load to the RAM, and, lastly and importantly, disabling the pre-loading privileges. This is similar to “real mode” in x86-64, where the booter runs in a privileged mode and later switches to “protected mode” for the actual OS, with the privileges taken away. This sub-circuit occupies the space equivalent to N_{pre} = ~1592 cycles in the circuit.

Boby sub-circuit: verify that, for the subsequent ~ 2^k - N_{pre} - N_{post} cycles, each cycle conforms to the behaviors of an RISC-V CPU. This is a highly repeated circuit, as each of the cycles here is equivalent to each other. Note that page loading and unloading are all done in the body. This is similar to the operating system taking care of the virtual memory and page management.

Post-loading sub-circuit: verify that the computation has been closed up properly, and close up the lookup tables for byte formality checking and RAM. This sub-circuit is placed exactly at the end of the circuit, and it takes space equivalent to N_{post} = ~6 cycles in the circuit. One can imagine this to be the machine powering-off itself.

In the RISC Zero GitHub repo, one can find the definitions of the body sub-circuit here.

Figure 4: The construction of the constraint system of the body phase of the zkVM.

And as one can see, the body sub-circuit is pretty simple, in that it just repeatedly writes “1” into the body wire of the underlying ZK circuit, until it is time to do post-loading.

Like other FRI proof systems, since FRI does not care about whether the circuit is sparse or dense, the proving generation overhead is entirely dependent on the size of the circuit, or more specifically, which one out of the six circuits above is being used.

Cycles are, in other words, the only thing that matters.

Note that recently, there has been discussion on proof systems that can leverage sparsity, such as Lasso + Jolt from a16zcrypto—which relies on committing structured multilinear extensions over homomorphic commitments—-and Binius from Ulvetanna—which is a binary proof system with hardware-friendly encoding. Both are relevant to RISC Zero. I personally consider Lasso + Jolt and Binius to be two separate cherry trees that contain very different, complementary techniques, and future versions of RISC Zero, or its community variants, can cherry-pick.

Since cycles are all we need to consider, we now turn our attention to tools that can help us study the cycles of a particular program.

A profiler that dives deep about cycles

As part of our research work, we built a profiler for RISC Zero, which we call profiler0.

https://github.com/l2iterative/profiler0

Remember that—to optimize the code, the first thing is to identify the major bottlenecks. The profiler0 tool enables us to add some timers into our code, as shown by “start_timer!”, “stop_start_timer!”, and “stop_timer!”, that verifies FHE in RISC Zero, as follows.

start_timer!("Total");

start_timer!("Load the bootstrapping key");

let bsk = black_box(unsafe {

std::mem::transmute::<&u8, &[GgswCiphertext; 16]>(&BSK_BYTES[0])

});

stop_start_timer!("Load the ciphertext to be bootstrapped");

let c = black_box(unsafe {

std::mem::transmute::<&u8, &LweCiphertext>(&C_BYTES[0])

});

stop_start_timer!("Perform trivial encryption and rotation");

let lut = black_box(GlweCiphertext::trivial_encrypt_lut_poly());

let mut c_prime = lut.clone();

c_prime.rotate_trivial((2 * N as u64) - c.body);

stop_start_timer!("Perform one step of the bootstrapping");

// set to one step

for i in 0..1 {

start_timer!("Rotate");

let rotated = c_prime.rotate(c.mask[i]);

stop_start_timer!("Cmux");

c_prime = cmux(&bsk[i], &c_prime, &rotated);

stop_timer!();

}

stop_timer!();

stop_timer!();This allows us to see how different parts of the code contribute to the number of cycles. The profiler follows the execution of the guest program and does statistics on the cycles. The result can be found here.

The result from the profiler can be summarized as follows.

Load the bootstrapping key: 15 instructions, 3,297 cycles

Load the ciphertext to be bootstrapped: 11 instructions, 11 cycles

Perform trivial encryption and rotation: 66,096 instructions, 123,982 cycles

Perform one out of the 1024 steps of bootstrapping: 151,619,979 instructions, 159,597,740 cycles

Rotate: 55,930 instructions, 75,670 cycles

Cmux: 151,564,031 instructions, 159,520,958 cycles

The total is 151,686,471 instructions and 159,726,565 cycles.

We can immediately draw some conclusions about where the cost comes from—cmux, as it accounts for 99% of the instructions and 99% of the cycles. Note that this is only a single step in the entire bootstrapping process. The entire TFHE bootstrapping example has 1024 such steps.

The natural next step of profiling is to go into the `cmux` function and have a breakdown. We add the following profiling codes into the TFHE library that we are using.

pub fn cmux(ctb: &GgswCiphertext, ct1: &GlweCiphertext, ct2: &GlweCiphertext) -> GlweCiphertext {

start_timer!("subtract the ciphertext");

let mut res = ct2.sub(ct1);

stop_start_timer!("external product");

res = ctb.external_product(&res);

stop_start_timer!("add the result");

res = res.add(ct1);

stop_timer!();

res

}And we also put in the profiling codes to the external_product function, which would be central to the performance. Note that the profiler accepts static messages as well as messages that are dynamically generated in the runtime.

impl GgswCiphertext {

/// Performs a product (GGSW x GLWE) -> GLWE.

pub fn external_product(&self, ct: &GlweCiphertext) -> GlweCiphertext {

start_timer!("apply g inverse");

let g_inverse_ct = apply_g_inverse(ct);

stop_start_timer!("multiply");

let mut res = GlweCiphertext::default();

for i in 0..(k + 1) * ELL {

start_timer!(format!("i = {}", i));

for j in 0..k {

res.mask[j].add_assign(&g_inverse_ct[i].mul(&self.z_m_gt[i].mask[j]));

}

res.body

.add_assign(&g_inverse_ct[i].mul(&self.z_m_gt[i].body));

stop_timer!();

}

stop_timer!();

res

}

}

This allows us to have a more detailed breakdown of the instructions from `cmux`, as shown below. Note that the profiler injects a few instructions, and so `cmux` cycle counts increase slightly.

Subtract the ciphertext: 38,495 instructions, 46,163 cycles

Apply G inverse: 79,991 instructions, 167,498 cycles

Multiply with i = 0: 37,840,587 instructions, 39,875,485 cycles

Multiply with i = 1: 37,840,584 instructions, 39,759,520 cycles

Multiply with i = 2: 37,840,584 instructions, 39,802,186 cycles

Add the result: 50,816 instructions, 70,525 cycles

The total is 151,565,973 instructions and 159,619,414 cycles.

The profiler also gives us the locations of the instructions that trigger a lot of cycles. One can find the same from the new output from the profiler here. Interestingly, a few locations appear extremely frequently, suggesting that it is in a loop.

0x200d18, 0x200d20, 0x200d74, 0x200d78, 0x200d7c

These addresses are close to each other, suggesting that they are likely the assembly code from a single function, and this function is being called repeatedly in a way that it contributes to the majority of the cycles. Although the profiler does show what that instruction is, for example, the 0x200d74 that pops up extremely frequently is “lw s10, t5, 0”, but to understand what an instruction is doing, we need context.

What is the best way to have context? There is a clear answer— “go back to the scene”.

Use GDB for dynamic code analysis

We need a tool that allows us to come back to the scene and see what is happening with the code. As part of our research work, we built a GDB stub for the RISC Zero guest program. The GDB stub is like the “glue code” that enables GDB to work with RISC Zero.

We call this GDB stub “gdb0”.

https://github.com/l2iterative/gdb0

To get started, we first compile the program with debug information. This is done by the following steps.

First, in the “guest” directory’s Cargo.toml, add the following so that even if we compile the program in the debug mode, it would still apply the necessary optimization (without which Rust programs would be unreasonably slow).

[profile.dev]

opt-level = 3

[profile.dev.build-override]

opt-level = 3Then, we compile the guest with an environment variable that turns on the RISC Zero debug mode.

RISC0_BUILD_DEBUG=1 cargo runThen, we copy-paste the compiled guest program, which is a standard ELF file for RISC-V code, into the gdb0 directory. The bash command to do this may differ in your local environment, but in our setup, we just do the following in the gdb0 directory. Be sure to copy the compiled program in the “debug” directory, not the “release” directory.

cp ../vfhe0/target/riscv-guest/riscv32im-risc0-zkvm-elf/debug/method codeWe should run the profiler again because the function may be in different locations. The new result from the profiler is attached here. We can see that addresses 0x200db0, 0x200db4, 0x200db8, 0x200dbc are instructions that often cause significant cycles (due to read/write).

We now start the GDB. To find more detail about how to get the GDB running, please refer to the GitHub repo above. We set a software breakpoint at 0x200db0 based on the profiler’s output above. Then, we ask GDB to continue the execution, ending up on the following screen.

Figure 5: Arriving at the loop that contributes to a lot of overhead.

This allows us to visualize why 0x200db0 is frequently being invoked and where it belongs. This is in the inner loop of the polynomial multiplication function. Note that when we set the breakpoint, GDB already tries to tell us that it corresponds to Line 42 of the “src/ttfhe/poly.rs” file.

We can see how the Rust source code translates to the RISC-V instructions. For example, this inner loop, which performs 64-bit integer multiplication, looks like this. Here, “bne” often refers to the end of the loop.

Figure 6: The inner loop that performs 64-bit integer multiplication and accumulation.

RISC Zero is using 32-bit RISC-V, and we can see that the 64-bit integer multiplication is being simulated by 32-bit integer operations, such as mul, mulhu, and add. This is done by Rust during compilation, and one can experiment with this and check the consistency in Godbolt.

Now that we can see through all the information about the execution of our program, and we have all the necessary tools for us to return to the scene, it is time to create an attack plan.

Diagnose our code

As we are coming to the end of our article, we want to talk about what we want to do in order to optimize the performance. This would also be the topic in subsequent articles in this series.

First, as the VFHE library disclaims, the current algorithm that performs negacyclic convolution is a very naive algorithm that runs in time O(n^2). In other words, when we do this on two vectors of size 1024, the code will need to perform 1048576 64-bit integer multiplication, as well as the cost to load/save data in the middle.

We know other algorithms. First of all, we rule out NTT because, since the modulus is 2^64 and we do not want to change it (in order to be compatible with Zama), there is not much hope for integer NTT. We could, however, like Zama, use floating point NTT over the complex numbers. The reason why Zama takes such a heavy-looking approach—using floating points—is simple: floating points are not expensive at all on modern CPUs, as it only takes a few cycles like integer multiplication, much cheaper than integer division.

This, however, is not the case for RISC-V or RISC Zero. The official document mentions that “floating point operations can take 60-140 cycles for basic operations such as add, subtract, multiply, and divide.” In RISC Zero, floating point operations are much more expensive. Based on our conversation with Rand Hindi from Zama, we conclude that a complex number NTT with floating point is likely not the solution for ZK.

The remaining option is non-NTT efficient polynomial multiplication (or, more specifically and precisely, negacyclic convolution). We plan to use the Karatsuba algorithm, which uses a divide-and-conquer manner to perform the computation, resulting in a subquadratic overhead.

This should already bring two orders of magnitude speedup.

Another opportunity of optimization is to find application-specific optimization opportunities. In TFHE, when we do the bootstrapping, we are multiplying a GGSW ciphertext to a GLWE ciphertext, and a very interesting thing about this multiplication is that GLWE would be decomposed into a format in which all the numbers are small (that is, applying the inverse G transform).

This means that we do not actually have to do 64-bit integer computation. The output of the inverse G transform, in our configuration, is only 8-bit. Karatsuba algorithm may add numbers here and there, so 16-bit representation should be comfortable as long as Karatsuba’s depth is not too large, to accommodate the intermediate results due to Karatsuba. In a 32-bit number, we can encode two of such numbers, which would save the memory space and load/save, and we can decode it on demand.

Lastly, let us go back to the inner loop and its assembly code.

Figure 6: The inner loop that performs 64-bit integer multiplication and accumulation.

The inner loop has about 20 instructions in each iteration. We can imagine that if we use the compressed representation discussed above, we can save a few instructions. Then, let us observe the rest of the instructions. There are a few quick observations.

0x200da4 - 0x200dac is a sanity check that detects if the code is accessing a location beyond the slice’s boundary. This is a Rust thing for safety. But, here, we may want to remove it.

0x200db4 - 0x200dc4, t4 is used to store the address of the rhs.coefs[N - j + i]. It seems very possible to simplify the computation rather than, for example, using “slli” to left-shift the value by 3 bits in order to multiply it by 8. We can have two pointers that move as the iteration progresses, one adding 8, one subtracting 8. This can be implemented around the code in 0x200df0 - 0x200df4.

If we use the compressed representation discussed above, it helps to do two steps in one iteration.

On average, each of the multiplications appears to contribute 36 cycles (=37840587 / 1024 / 1024). We shall be able to reduce this number through such optimization, and since Karatsuba can reduce the number of multiplications, we can reduce the total multiplication overhead.

An interesting idea is to see if we can use the RISC Zero bigint syscall to simulate three 16-bit times 64-bit computation, but it is uncertain if it would be more efficient because there would be overhead to pack and unpack.

Lastly, if we want to build the entire proof (for 1024 steps) within a reasonable amount of time, we need to have some acceleration: hardware acceleration and software acceleration. We will experiment with RISC Zero’s Metal GPU optimization, which appears to be very powerful, and we will look at RISC Zero’s continuation and how we can generate the proof for the entire computation in parallel, so that we can scale linearly to reduce the latency.

We are also particularly interested in RISC Zero’s Zirgen tool, which may open up the possibility of customized proof systems that add a vectorized instruction specifically to help with negacyclic convolution. Another thing to look into is a probabilistic checking protocol from Jeremy Bruestle, discussed in RISC Zero Discord, which gives O(n) complexity, but the detail still needs to be worked out.

Long story short, see you in the next article in the RISC Zero series for verifying FHE.

Find L2IV at l2iterative.com and on Twitter @l2iterative

Author: Weikeng Chen, Research Partner, L2IV (@weikengchen)

Disclaimer: This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisors as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services.