Tech Deep Dive: Verifying FHE in RISC Zero, Part I

From Hidden to Proven: The ZK Path of FHE Validation

We recently looked into verifying FHE using zero-knowledge proofs (ZKP) because it is crucial in two emerging use cases.

Off-chain computation for fhEVM: Fhenix and Inco are working on L1 chains that augment EVM with fully homomorphic encryption based on Zama’s fhEVM, where fhEVM stands for fully homomorphic Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). Off-chain computation can save validators from the need to rerun FHE computation (scalability) and may be able to further hide the functions (privacy).

FHE mining: Inspired by Aleo’s proof of succinct work (PoSW) and the ZPrize initiatives, we consider FHE mining to be a notable future direction to encourage ASIC manufacture for FHE and incentivize FHE miners to become validators for fhEVM networks. The core task of FHE mining is to develop a ZKP system for PoSW in FHE contexts.

Among the different FHE schemes, we are particularly interested in TFHE that Zama used. This implementation of TFHE uses a modulus p = 2^64, selected for its computational efficiency on modern CPUs and other hardware platforms. Our interest in verifying FHE in this setting stems from its immediate applicability in fhEVM.

However, employing a modulus of p = 2^64 presents significant challenges for ZKPs, as there are limited zero-knowledge proof systems effectively compatible with this modulus.

Most zero-knowledge proof systems are designed to operate within a field, but modulus p = 2^64 does not form a field, as exemplified by the lack of a modular inverse for 2, making it merely a ring. We have a zero-knowledge proof system called Rinocchio that is designed for rings, but it does not work here because it only supports (1) arbitrary rings if the ZKP is designated-verifier, which is not suitable for blockchain applications and (2) rings associated with secure, composite-order pairing-friendly curves, which would not be compatible with p = 2^64.

Alternatively, using a suitable field to simulate 64-bit integer computations is an option, though it comes with its own set of costs. There are only a few VMs that have been designed with 64-bit integers, including RISC Zero and Aleo’s Leo. It's also feasible to simulate 64-bit integer computations from 32-bit ones, thereby broadening VM support options to include platforms like Polygon Miden (see this Miden assembly file for example) and Valida.

We pick RISC Zero for three reasons.

The toolchain and the development ecosystem are notably stable and mature.

The performance of proof generation on RISC Zero, especially when utilizing Apple M2 chips, as we do at L2IV, is impressively decent.

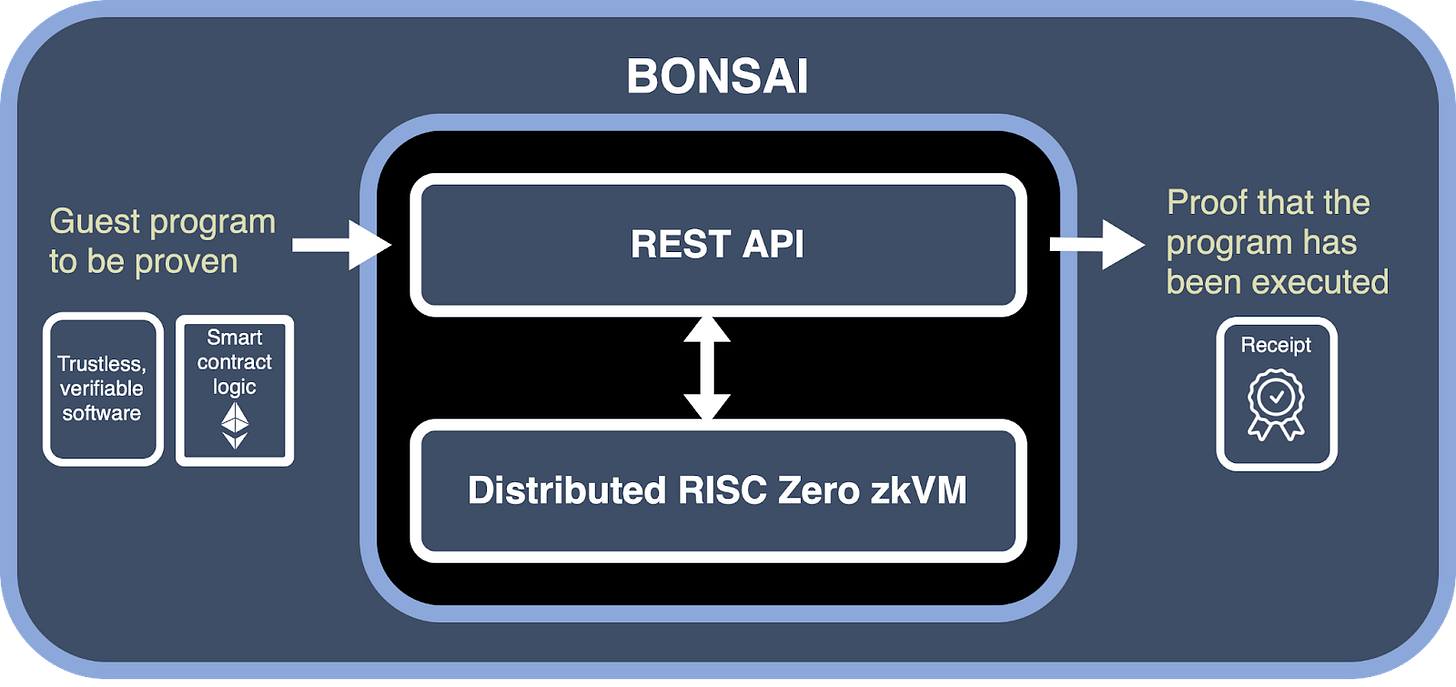

We happen to have a highly coveted and limited Bonsai API key that allows us to offload the proof generation process to RISC Zero’s dedicated Bonsai servers, thereby alleviating the need for local proof generation.

Figure 1: RISC Zero’s Bonsai delegated proof generation services.

This article, Part I, will document our journey towards achieving a functional yet unoptimized prototype. In the subsequent articles, we will delve into our efforts to optimize the implementation. Additionally, we will explore various future directions inspired by our insightful conversations with RISC Zero developers.

What is TFHE?

To understand TFHE, it's essential to first grasp the concept of fully homomorphic encryption (FHE). At its core, FHE is an encryption algorithm, denoted as E, designed for data encryption. For example, given a plaintext a, encryption gives us the ciphertext E(a).

The full homomorphism means that we can compute over the ciphertexts, including additions, subtractions, and multiplications.

When the plaintexts are binary bits (0 and 1), it becomes possible to represent all binary logic gates using FHE. This includes fundamental gates like XOR and AND, as they form the basis of any binary logic operations in FHE.

Given its capability to represent all binary gates, FHE is thus able to perform arbitrary computations within a bounded size. In blockchain applications, FHE is garnering significant interest for enabling privacy in decentralized finance (DeFi) applications. For instance, in privacy-enhanced decentralized exchanges (DEXs), FHE can confidentially handle computations for automated market makers (AMMs).

A major portion of the computational overhead in FHE is attributed to managing and mitigating 'noise'. All existing FHE constructions rely on the learning-with-error (LWE) assumption or its variants, which form the foundational basis of these cryptographic systems. And for each step of the computation, the output—such as E(a + b - a × b)—will have more noise than the inputs E(a) and E(b), and this output may become the input for subsequent steps. As computations progress, the ciphertexts accumulate increasingly larger amounts of noise. As depicted in Figure 2, once the noise in a ciphertext reaches a certain threshold, it renders the ciphertext undecryptable.

Figure 2: An illustration of the noise in FHE, extracted from a paper of Marc Joye (Zama).

To facilitate unbounded computation in FHE, it's essential to find a method for clearing the noise before it becomes excessively large. This technique, known as 'bootstrapping', was first introduced by Craig Gentry in 2009 through his groundbreaking paper on FHE. Bootstrapping involves using an encrypted version of the FHE secret key, often referred to as the 'bootstrapping key', to decrypt and thereby refresh a noisy ciphertext, which results in a new ciphertext that contains the same data, but with less noise.

One can imagine FHE computation to be a very exhausting exercise—like a marathon—for the ciphertext, and the ciphertext needs to take breaks in order to avoid “burnout”, as we illustrate in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Think of FHE bootstrapping as a person needing to take a break in order to avoid burnout in a marathon (illustration by Midjourney).

Among different fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) algorithms, TFHE has garnered significant attention because bootstrapping in TFHE is efficient, and TFHE is very suitable for evaluating Boolean circuits over encrypted data. Zama, Fhenix, Inco are all using TFHE.

Therefore, a principal challenge in verifying FHE lies in accurately validating the bootstrapping process. In TFHE, bootstrapping involves using a bootstrapping key to 'blindly rotate' a polynomial in line with the ciphertext being bootstrapped, subsequently extracting a refreshed ciphertext from this rotated polynomial.

While this might initially seem like a foray into advanced cryptography, it's reassuring to note that the process predominantly revolves around manipulating polynomials and matrices, as shown by Figure 4, which is extracted from Marc Joye’s primer on TFHE. For those keen on delving deeper, we highly recommend this primer by Marc Joye on TFHE, which is approachable for those with just a basic understanding of linear algebra.

Figure 4: A summary of the bootstrapping algorithm in TFHE from Marc Joye’s primer.

Now that we have some basic background about FHE, let’s explore how RISC Zero can be useful here.

What is RISC Zero?

RISC Zero is a versatile zero-knowledge proof system specifically designed for RISC-V architecture. In other words, any program that can be compiled into an ELF (executable and linkable format) program over riscv32im (RISC-V 32 bit with the “M” extension for integer multiplication and division) is compatible with RISC Zero. Upon execution by the VM, RISC Zero generates a zero-knowledge proof of this execution, termed as a 'receipt'. Figure 5 illustrates this process.

Figure 5: The workflow of RISC Zero.

A frequently asked question about RISC Zero is its preference for RISC-V over other instruction sets. We find two key reasons.

First, RISC-V has a simple but universal instruction set. RISC Zero only needs to support the following 46 instructions from riscv32im.

LB, LH, LW, LBU, LHU, ADDI, SLLI, SLTI, SLTIU, XORI, SRLI, SRAI, ORI, ANDI, AUIPC, SB, SH, AW, ADD, SUB, SLL, SLT, SLTU, XOR, SRL, SRA, OR, AND, MUL, MULH, MULSU, MULU, DIV, DIVU, REM, REMU, LUI, BEQ, BNE, BLT, BGE, BGEU, JALR, JAL, ECALL, EBREAK

This is much simpler from modern Intel x86—which has 1131 instructions, and modern ARM can be up to hundreds of instructions. RISC-V is also not too different from other minimalistic instruction sets—MIPS (the company of MIPS later transitioned into working on RISC-V), WASM, and very early generations of ARM such as ARMv4T.

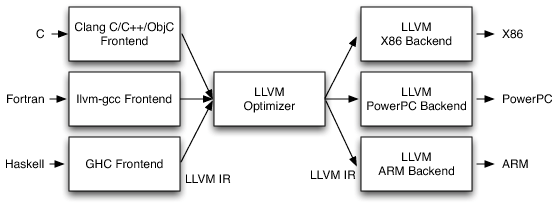

Second, it is easy to compile various languages to RISC-V, thanks to LLVM. LLVM is a compilation toolchain that implements an intermediary layer (called “intermediate representation”) between the backends (“ISAs”) and the frontends (“programming languages”). Since RISC-V is one of the supported backends, LLVM allows the many frontends—including C, C++, Haskell, Ruby, Rust, Swift, and so on to be compiled into RISC-V.

Figure 6: LLVM’s three-phase design (illustration from Chris Lattner’s book), where RISC-V is also an available LLVM backend.

In other words, through a bottom-up approach, RISC Zero is able to support programs that are written using existing, Web2 programming languages. One can also build their own ZKP domain-specific language (DSL)—which can include ZoKrates, Cairo, Noir, and Circom—and create a compiler that converts them into RISC-V. For languages where direct compilation to RISC-V is challenging, an alternative approach is to first compile the DSL into an intermediate language like C/C++, and then use an existing LLVM compiler for the final conversion to RISC-V.

Another question people would ask is, why, despite RISC-V being a favorable choice, we initiate with a virtual machine? Can’t we just write the “constraint system” in an existing ZK-specific DSL, such as ZoKrates, Cairo, Noir, and Circom?

There are two reasons.

Firstly, using RISC Zero significantly reduces development time. Traditionally, crafting the constraint system for ZKPs was a laborious task that can only be done by skillful developers, and it can take weeks. What’s worse is that debugging the constraint system can take even longer, and it is hard to make sure that the constraint system is bug-free. This has been one of the factors that limit the development and adoption of zero-knowledge proofs—because it is hard to build applications.

It can be once an ambitious startup project to build historical proofs that verify the history of Bitcoin or Ethereum, or prove the output of an AI game bot in zero knowledge. Now, with RISC Zero, what was once an ambitious endeavor becomes feasible even as a hackathon project. For instance, verifying Zama’s FHE—an application that is very complicated and no one has ever written the ZKP constraint system for it before—can be done in RISC Zero with a few lines of the code.

This shift also simplifies the process of recruiting developers. A person who has previous experience in Rust can easily migrate an existing piece of Rust code into RISC Zero, and this person does not even need a lot of Rust knowledge.

Secondly, RISC Zero may even surpass human performance in certain aspects. The key strength of RISC Zero lies in that it has been specifically optimized to do 32-bit and 64-bit integer computation as well as manage a large storage and memory, and even a skillful ZKP engineer cannot beat it.

Before RISC Zero, performing such optimization required top-notch ZKP researchers and engineers, as such techniques are extremely recent and were never documented. The optimization requires at least months to develop, as it requires probably the most creative usage of the lookup arguments.

RISC Zero has encapsulated these cutting-edge technologies into its Bonsai framework, making them both accessible and affordable. If cryptography is like cooking, then RISC Zero is a microwave oven.

Returning to our initial discussion, let's explore how RISC Zero can be utilized to verify Zama’s FHE computation in zero knowledge. It appears that all it takes from us is reusing some code from Zama’s team and then adding a few lines of code.

The code

In this first part of our series, we demonstrate how to verify the main step of bootstrapping an FHE ciphertext: using a bootstrapping key to perform a “blind rotation” of a polynomial, as follows.

#![no_main]

risc0_zkvm::guest::entry!(main);

// load the toy FHE Rust library from Louis Tremblay Thibault (Zama)

use ttfhe::{N,

ggsw::{cmux, GgswCiphertext},

glwe::GlweCiphertext,

lwe::LweCiphertext

};

// load the bootstrapping key and the ciphertext to be bootstrapped

static BSK_BYTES: &[u8] = include_bytes_aligned!(8, "../../../bsk");

static C_BYTES: &[u8] = include_bytes_aligned!(8, "../../../c");

pub fn main() {

// a zero-copy trick to load the key and the ciphertext into RISC Zero

let bsk = unsafe {

std::mem::transmute::<&u8, &[GgswCiphertext; N]>(&BSK_BYTES[0])

};

let c = unsafe {

std::mem::transmute::<&u8, &LweCiphertext>(&C_BYTES[0])

};

// initialize the polynomial to be blindly rotated

let mut c_prime = GlweCiphertext::trivial_encrypt_lut_poly();

c_prime.rotate_trivial((2 * N as u64) - c.body);

// perform the blind rotation

for i in 0..N {

c_prime = cmux(&bsk[i], &c_prime, &c_prime.rotate(c.mask[i]));

}

eprintln!("test res: {}", c_prime.body.coefs[0]);

}Excluding the lines of code for trivial operations such as loading dependencies or constant data, the actual number of lines of code is just 5—encompassing the initialization of the polynomial and blindly rotating it.

let mut c_prime = GlweCiphertext::trivial_encrypt_lut_poly();

c_prime.rotate_trivial((2 * N as u64) - c.body);

for i in 0..N {

c_prime = cmux(&bsk[i], &c_prime, &c_prime.rotate(c.mask[i]));

}The key functions and algorithms executing the FHE steps, including `trivial_encrypt_lut_poly`, `rotate_trivial`, and `cmux`, come directly from the toy FHE Rust library (ttfhe), developed by Louis Tremblay Thibault at Zama.

Utilizing RISC Zero, we're able to generate a proof for the execution of this RISC-V program. The code below from RISC Zero executes the RISC-V program (an executable file in the ELF format) and generates a proof (called “receipt”) that certifies the execution. Let's examine the code snippet to understand how it accomplishes these tasks:

let env = ExecutorEnv::builder().build().unwrap();

let prover = default_prover();

let receipt = prover.prove_elf(env, METHOD_NAME_ELF).unwrap();

receipt.verify(METHOD_NAME_ID).unwrap();The receipt can be transmitted to a third party who can then verify the execution of the RISC-V program without gaining access to its detailed workings. For situations requiring more compact proof formats, RISC Zero also has the capability to generate a succinct proof, which retains its verifiability while being more concise.

Starting point: VFHE from Louis Tremblay Thibault

Our starting point is the toy FHE Rust library (https://github.com/tremblaythibaultl/ttfhe/) by Louis Tremblay Thibault, who is a research engineer in Zama. This library is pretty suitable for two reasons.

It is very close to Zama’s library that has been used in fhEVM in production.

It is written in Rust, which facilitates straightforward compilation to RISC-V.

Figure 7: Louis’s toy FHE Rust library.

The toy FHE Rust library is minimalistic—it only has 6 files and contains 800 lines of code—but it has full-fledged support for three different types of FHE ciphertexts that we will use.

LWE ciphertexts (lwe.rs), the structure of which here is a vector of 1024 64-bit integers.

General LWE (GLWE) ciphertexts (glwe.rs), the structure of which here is also a vector of 1024 64-bit integers.

General Gentry–Sahai–Waters (GGSW) ciphertexts (ggsw.rs), the structure of which here is a matrix of 64-bit integers of size 4 x 1024.

This suffices for initiating our development with RISC Zero, as our primary requirement is an efficient Rust implementation that seamlessly compiles down to RISC-V. has developed a preliminary version of these concepts in the VFHE library (https://github.com/tremblaythibaultl/vfhe), serving as our foundational starting point.

#![no_main]

use risc0_zkvm::guest::env;

use ttfhe::{ggsw::BootstrappingKey, glwe::GlweCiphertext, lwe::LweCiphertext};

risc0_zkvm::guest::entry!(main);

pub fn main() {

// bincode can serialize `bsk` into an blob that weighs 39.9MB on disk.

// This `env::read()` call doesn't seem to stop - memory is allocated until the process goes OOM.

let (c, bsk): (LweCiphertext, BootstrappingKey) = env::read();

let lut = GlweCiphertext::trivial_encrypt_lut_poly();

// `blind_rotate` is a quite heavy computation that takes ~2s to perform on a M2 MBP.

// Maybe this is why the process is running OOM?

let blind_rotated_lut = lut.blind_rotate(c, &bsk);

let res_ct = blind_rotated_lut.sample_extract();

env::commit(&res_ct);

}However, this represents merely a starting point, as there are two significant issues highlighted by comments within the code.

The first issue pertains to data loading. We face a yet unresolved challenge in efficiently loading the bootstrapping key and the ciphertext—which can be of a significant size—into the RISC-V program.

Louis’s approach is to use RISC Zero’s `env::read` channel, which is a standard approach for feeding data externally into the RISC-V machine during proof generation. However, as Louis noted, this method is not optimal, primarily due to its significant memory requirements and the extensive VM CPU cycles needed just for data loading, leading to out-of-memory (OOM) issues. Parker Thompson at RISC Zero acknowledged that this could likely be the source of the issue: “Generally reading large chunks of data into the guest is pretty costly.” (Here, the guest refers to the RISC-V program for which a proof would be generated.)

As a preliminary solution to circumvent this data loading overhead, we propose embedding the data directly within the RISC-V program. In Rust, a typical solution involves the `include_bytes_aligned!` macro, instructing the compiler to integrate the data into the RISC-V executable. Subsequently, we can deserialize this data from the bytes, for instance, using `bincode::deserialize`. The code looks like the following.

static BSK_BYTES: &[u8] = include_bytes_aligned!(8, ("../../../bsk");

let bsk: BootstrappingKey = bincode::deserialize(BSK_BYTES);However, a significant challenge arises from the extensive cycles required by the RISC-V program to allocate memory and copy data for the entire 64MB bootstrapping key. Our benchmark shows that it would take at least 2 hours just to prove the correct loading of the key.

In this article, we unveil a 'zero-copy' trick within RISC Zero that addresses this issue. It allows us to materialize the bootstrapping key incurring almost zero CPU cycles. We'll delve into the details of this technique shortly in this article.

The second major issue concerns computation. As Louis commented on the code, the efficiency of blind rotation (which is the main step of bootstrapping) can be a problem because it is not a lightweight computation itself (“takes 2s to perform on a M2 MBP”). This is the larger challenge of the entire “verifying FHE in RISC Zero”.

We have designed and implemented a number of tricks and techniques in RISC Zero to optimize this part. This journey into optimizing FHE computation in RISC Zero is extensive, and we plan to dedicate several articles in this series to thoroughly explain each trick and technique. Stay tuned for the forthcoming articles in this series! To ensure you don’t miss out, consider subscribing to our Substack.

A zero-copy trick to load a large amount of data

In this section, we delve into our approach to overcoming the data loading challenge in the RISC-V program, emphasizing methods that significantly reduce RISC-V CPU cycles.

The core idea is to avoid copying data in the RISC-V. This is crucial because copying a 64MB data set in RISC-V would necessitate upwards of 50 million instructions—one instruction to read data, one instruction to write data, and one instruction to update the pointer. All of these instructions are to some extent, unnecessary, because the data is already available as the Rust compiler has included it as part of the RISC-V program.

Implementing this in Rust is challenging due to its inherent design for memory safety. The standard practice in Rust involves initializing data structures through a stringent process: allocate the data structures in the stack or in the heap, zeroize the memory of the data structures (by pedantically filling in that entire memory with zeros), and copy the data one after the other. One can see that Rust is spending the computation cycles even more lavishly because zeroizing the memory is going to take another 34 million instructions at the minimum.

Our solution employs certain low-level Rust primitives that allow us to “bypass” the restrictions imposed by the Rust LLVM compiler, thus programming the RISC-V more efficiently.

During my collaboration with Greater Heat on Aleo mining, I learned a valuable technique involving 'std::mem::transmute'." This is a special Rust function that reinterprets the bits of one type to another type. In particular, it can be used to modify the types of a pointer.

For our application, we explicitly embed (or, more accurately, hardcode) the bytes of the memory regions for the bootstrapping key (BSK_BYTES) and the ciphertext to be bootstrapped (C_BYTES) directly in the RISC-V files. To avoid the need to copy the data, we directly manipulate the type of the pointer, as follows.

let bsk = unsafe {

std::mem::transmute::<&u8, &[GgswCiphertext; N]>(&BSK_BYTES[0])

};

let c = unsafe {

std::mem::transmute::<&u8, &LweCiphertext>(&C_BYTES[0])

};As demonstrated in the preceding code, we obtain the ELF segment pointer to the hardcoded data, initially a byte pointer (`&u8`). We then transform this into either a pointer to a bootstrapping key (`&[GgswCiphertext; N]`) or a pointer to the LWE ciphertext (`&LweCiphertext`). Furthermore, it's necessary to encapsulate this code within an `unsafe` bracket as Rust categorizes this low-level function as unsafe and mandates explicit acknowledgment of its potential risks via unsafe. This use of unsafe doesn’t inherently imply danger; rather, it signifies the need for specialized expertise in handling such low-level operations.

For readers familiar with C/C++, this process can be likened to typecasting. In C/C++, the equivalent code would appear as follows.

/* C */

BootstrappingKey *bsk = (BootstrappingKey*) &BSK_BYTES[0];

LweCiphertext *c = (LweCiphertext*) &C_BYTES[0];

/* C++ */

BootstrappingKey *bsk = reinterpret_cast<BootstrappingKey*>(&BSK_BYTES[0]);

LweCiphertext *c = reinterpret_cast<LweCiphertext*>(&C_BYTES[0]);Our experimental results reveal that the number of cycles typically consumed by data loading is virtually eliminated using this approach. In the forthcoming analysis, we will further validate this zero-copy operation through the use of an RISC-V decompiler.

Look at the RISC-V

We have addressed the initial challenge encountered by Louis from Zama in using RISC Zero for FHE bootstrapping verification. In the upcoming articles of this series, we will delve deeper into the topic of performance improvement and its nuances.

As we conclude this first part, our next step involves using an RISC-V decompiler to examine the program verified by RISC Zero in a zero-knowledge context. Our objectives are twofold:

Confirm that our technique effectively achieves zero-copy at the RISC-V assembly level.

Gain a comprehensive understanding of the overall structure of our RISC-V program.

For this purpose, we utilize Ghidra (https://github.com/NationalSecurityAgency/ghidra), a comprehensive, free-to-use reverse engineering framework developed by the US National Security Agency (NSA), which notably includes support for RISC-V.

Figure 8: Ghidra’s CodeBrowser on the RISC-V program that RISC Zero is proving.

Ghidra allows us to see both the RISC-V assembly code—as displayed in the middle pane—and the decompiled code (presented in C)---as shown on the right. Reflecting on our previous mention of RISC-V's 46 instructions, it's noteworthy that the assembly code we're analyzing utilizes these exact instructions.

We will now focus on the automatically generated decompiled code, presented below, for a detailed analysis.

/* method_name::main */

void method_name::main(void)

{

uint *puVar1;

uint *puVar2;

int iVar3;

undefined auStack_c018 [8192];

undefined auStack_a018 [8192];

undefined *local_8018;

code *local_8014;

int *local_4018 [2];

undefined1 *local_4010;

undefined4 local_400c;

undefined **local_4008;

undefined4 local_4004;

gp = &__global_pointer$;

ttfhe::glwe::GlweCiphertext::trivial_encrypt_lut_poly(auStack_c018);

ttfhe::glwe::GlweCiphertext::rotate_trivial((int)auStack_c018,0x600);

puVar2 = &anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.1.llvm.4718791565163837729;

puVar1 = (uint *)&anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.0.llvm.4718791565163837729;

iVar3 = 0x400;

do {

ttfhe::glwe::GlweCiphertext::rotate(local_4018,(int)auStack_c018,*puVar2);

ttfhe::ggsw::cmux(&local_8018,puVar1,(int)auStack_c018,(int)local_4018);

memcpy(auStack_c018,&local_8018,0x4000);

puVar2 = puVar2 + 2;

iVar3 = iVar3 + -1;

puVar1 = puVar1 + 0x4000;

} while (iVar3 != 0);

local_8018 = auStack_a018;

local_8014 = u64>::fmt;

local_4010 = anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.4.llvm.4718791565163837729;

local_400c = 2;

local_4018[0] = (int *)0x0;

local_4008 = &local_8018;

local_4004 = 1;

std::io::stdio::_eprint(local_4018);

return;

}Our initial observation confirms that the data loading process indeed achieves zero-copy efficiency. The code segment utilizing `std::mem::transmute` for data loading compiles into a 16-byte sequence of RISC-V machine codes:

37 c5 20 04 93 04 c5 4c 37 c5 20 00 13 04 c5 4c

Decompilation reveals four assembly instructions, responsible for storing the pointer values into the s1 and s0 registers. Essentially, this code assigns the value 0x420c4cc to the s1 register and 0x020c4cc to the s0 register.

00200844 37 c5 20 04 lui a0,0x420c

00200848 93 04 c5 4c addi s1,a0,0x4cc

0020084c 37 c5 20 00 lui a0,0x20c

00200850 13 04 c5 4c addi s0,a0,0x4cc

Next, we can further decompile this assembly code into a C-like format for a clearer understanding, as demonstrated below.

uint *puVar1;

uint *puVar2;

puVar2 = &anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.1.llvm.4718791565163837729;

puVar1 = (uint *)&anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.0.llvm.4718791565163837729;In the decompiled code, the first label—anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.1.llvm.4718791565163837729—specifically indicates the location of the ciphertext bytes, denoted as C_BYTES. Utilizing Ghidra, we are able to directly observe these ciphertext bytes within the code.

Figure 9: The ELF executable file’s data at location 0x420c4cc (i.e., the s1 register’s initial value), which is for the ciphertext to be bootstrapped.

Recall that C_BYTES is incorporated from a file named `c`. By employing Hex Fiend, a tool for hex editing, we can examine the contents of this file. The examination, as depicted below, confirms the consistency of the data.

static C_BYTES: &[u8] = include_bytes!("../../../c");Figure 10: The “c” file that stores the ciphertext to be bootstrapped, shown in a hex editor.

In a similar vein, by navigating to the second label—anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.0.llvm.4718791565163837729—we can locate the bytes corresponding to the bootstrapping key, referred to as BSK_BYTES.

Figure 11: The ELF executable file’s data at location 0x020c4cc (i.e., the s0 register’s initial value), which is for the bootstrapping key.

Additionally, we can validate this data by cross-checking it with its source file, 'bsk', ensuring that it aligns with the information presented above.

Figure 10: The “bsk” file that stores the bootstrapping key, shown in a hex editor.

Moving forward, let's explore how the key and ciphertext are utilized within the program. Recall from the Rust source code that both the key and ciphertext are integral in the for loop, specifically in the invocation of the `cmux` function.

// perform the blind rotation

for i in 0..N {

c_prime = cmux(&bsk[i], &c_prime, &c_prime.rotate(c.mask[i]));

}Now, let's turn our attention to Ghidra to locate and examine the corresponding decompiled code.

puVar2 = &anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.1.llvm.4718791565163837729;

puVar1 = (uint *)&anon.874983810a662adbf4687c54e184621b.0.llvm.4718791565163837729;

iVar3 = 0x400;

do {

ttfhe::glwe::GlweCiphertext::rotate(local_4018,(int)auStack_c018,*puVar2);

ttfhe::ggsw::cmux(&local_8018,puVar1,(int)auStack_c018,(int)local_4018);

memcpy(auStack_c018,&local_8018,0x4000);

puVar2 = puVar2 + 2;

iVar3 = iVar3 + -1;

puVar1 = puVar1 + 0x4000;

} while (iVar3 != 0);The decompiled code involves various components.

Cursor Assignments:

puVar2serves as the current cursor pointing toc, whilepuVar1is aligned withbsk. This setup facilitates the navigation through the ciphertext and the bootstrapping key.Loop Mechanics: The loop utilizes

iVar3, a decrementing counter starting from 1024, which signals the loop's termination upon reaching zero. Within each iteration, several operations are performed:

Ciphertext Manipulation:

c_prime, stored inauStack_c018on the stack, is first rotated withc.mask[i](referred to as*puVar2) to yield a result placed inlocal_4018.`cmux` Function Invocation: This key function takes

bsk[i](puVar1), the originalc_prime, and the rotatedc_primeas inputs, outputting the result intolocal_8018.

Optimization Opportunity: An intriguing aspect is the handling of

local_8018, which is treated as the updatedc_prime. It is copied back into thec_primevariable, hinting at a potential optimization. Eliminating this copy by performingcmuxin an in-place manner could enhance efficiency.Cursor Updates: The loop includes updates to both

puVar2andpuVar1.puVar2moves forward by two dwords (64 bits) to the nextc.mask[i], whilepuVar1advances by 16384 dwords (524288 bits) to the subsequentbsk[i].

As the loop concludes when iVar3 reaches zero, these steps collectively represent the process of handling the FHE bootstrapping in the RISC-V program.

Further analysis using Ghidra enables us to scrutinize other segments of the program, providing insights into potential optimization opportunities. This process helps us assess whether the Rust RISC-V compiler is generating RISC-V instructions as intended.

For instance, let’s examine the decompiled code of the cmux function. To provide context, we’ll first consider the original Rust code as follows.

/// Ciphertext multiplexer. If `ctb` is an encryption of `1`, return `ct1`. Else, return `ct2`.

pub fn cmux(ctb: &GgswCiphertext, ct1: &GlweCiphertext, ct2: &GlweCiphertext) -> GlweCiphertext {

let mut res = ct2.sub(ct1);

res = ctb.external_product(&res);

res = res.add(ct1);

res

}The decompiled code reveals that function calls to `sub` and `add` have been effectively inlined during compilation. This inlining results in visible loops within the code, which are responsible for simulating 64-bit integer operations. Additionally, the code utilizes several calls to `memset` and `memcpy`. Notably, some instances of `memset` are employed for zeroizing memory, which may not always be necessary. This observation opens up potential optimization avenues, particularly in eliminating unnecessary `memset` calls.

Figure 11: Decompiled code of the RISC-V instructions of the `cmux` function.

With this, we conclude Part I of our technical deep dive into verifying FHE in RISC Zero. This article provided an overview of FHE and RISC Zero, detailed the process of adapting existing Rust code for RISC Zero, introduced a novel data loading optimization trick in RISC Zero, and demonstrated the use of Ghidra for disassembling and analyzing RISC-V code to identify further optimization opportunities.

Keep an eye out for the upcoming articles in our 'Verifying FHE in RISC Zero' series, where we will delve deeper into more advanced concepts and optimizations.

Update on 12/14/2023: We notice that `include_bytes` may fail to align the data properly and can cause an alignment error. Therefore, we opt to use `include_bytes_aligned` from this crate.

Find L2IV at l2iterative.com and on Twitter @l2iterative

Author: Weikeng Chen, Research Partner, L2IV (@weikengchen)

Disclaimer: This content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisors as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services.